News - Feature Stories - Magazine

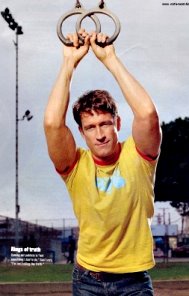

- Robert Gant

Robert Gant works it out

What was your religious upbringing?

Well, my mom was both Catholic and a Christian Scientist, depending

on which family she was spending time with. And my dad’s background was

Catholic. They didn’t have any particular religious preference at the

time that I was raised, but I went to the Baptist church because we lived close

to one and my peers went there.

You went without your parents to the Baptist church?

It was my brother and I going on our own. We were baptized there.

Because that’s where your friends went?

Yeah. So that was really my greatest religious background or

underpinning—the Baptist church. And I went to an Episcopalian school

in seventh and eighth grade and a Catholic school in ninth grade. Got the hell

out of there and went to public schools. And when I first arrived at Chamberlain

[the public school, in 10th grade], I remember realizing that I knew fewer than

a handful of people—fewer than I could count on one hand—and deciding

that the big thing was homecoming. I decided that I was going to be homecoming

king my senior year.

And what do you do in 10th grade to become homecoming king in

12th?

Well, you look at how the voting works and you look and see that

it’s the whole school that votes and not just your class—it sounds

so Machiavellian—but I felt like I had to be [homecoming king]. I just

so much wanted to be OK.

How’d you end up doing television commercials when you were

10?

My mom. I started taking tap and jazz back when I was in fifth

grade…fourth grade? I think my mom just recognized from a very early age

that I was sort of a precocious kid. She said that when I was 3, I had every

commercial on television memorized and I used to recite them all. I used to

get up in front of any company that we had—prompted somewhat by my mother

but ultimately not really needing to be that prompted—to sing some song.

So at some point I think she recognized that I had some sort of a desire or

an interest in this, and so she took me to meet a couple of agents. They sent

me on a few things and I booked them—whatever commercials I went on. So

that’s how I got started. I remember my first taste of [celebrity:] I

just remember in the fifth grade all of the kids at school [saying,] “I

saw you on TV!” That shock of having seen me on cereal commercials.

Do you remember the cereal?

Yeah,

the first one was Frankenberry, Boo Berry, and Count Chocula—the monster

cereals. And then there was a Cheerios commercial. And Frankenberry, at the

time they had Battlestar Galactica cards in the box, and so my first line on

camera was, “Viper Fighters in battle!” And then the little girl—who

ended up being one of the girls in the movie Annie—said, “Mine’s

the Battlestar under attack!” And then my second line was, “Let’s

trade!” So that was my first intro to the world of television.

Yeah,

the first one was Frankenberry, Boo Berry, and Count Chocula—the monster

cereals. And then there was a Cheerios commercial. And Frankenberry, at the

time they had Battlestar Galactica cards in the box, and so my first line on

camera was, “Viper Fighters in battle!” And then the little girl—who

ended up being one of the girls in the movie Annie—said, “Mine’s

the Battlestar under attack!” And then my second line was, “Let’s

trade!” So that was my first intro to the world of television.

How did you get from there to here?

When I was in high school—actually, right after I graduated—I

got a Toyota commercial over in Miami. And I met with a couple of agents, and

they said, “You really need to change your name.” They kept saying

this to me over and over again: “Because you just don’t look like

a Gonzalez.” That summer I filed a change with the Screen Actors Guild,

which I joined back in fifth or sixth grade, and promptly forgot about it. I

went off to college, and a number of times almost just let my card expire because

I never saw that as my future.

I remember I was in high school, and I was in a pop singing group.

The wonderful director we had—Chuck Robinson is the name of the guy; I

have to track him down to thank him—one day he pulled me into his office,

and it was just this really unexpected conversation. He said, “You know,

Bobby, I really hope you’re going to pursue this.” It was this really

unexpected interest in me that I just didn’t know was there because he

had never shown it in any way, and all of a sudden he was having this heart-to-heart

with me. And I remember not knowing what to say; I remember feeling bad for

him because he didn’t get it. He didn’t realize that it just wasn’t

a viable option, and so I tried to very kindly tell him, “I gotta make

money—I can’t go and wait tables.” These were the things that

I had going on in my head; these were the lessons that I had learned. So as

much as this was my passion and my dream, I was resigned to the fact that it

wasn’t to be. What a potential tragedy!

Page 1

. 2 . 3 .

4 . 5 . 6

. [7]

Yeah,

the first one was Frankenberry, Boo Berry, and Count Chocula—the monster

cereals. And then there was a Cheerios commercial. And Frankenberry, at the

time they had Battlestar Galactica cards in the box, and so my first line on

camera was, “Viper Fighters in battle!” And then the little girl—who

ended up being one of the girls in the movie Annie—said, “Mine’s

the Battlestar under attack!” And then my second line was, “Let’s

trade!” So that was my first intro to the world of television.

Yeah,

the first one was Frankenberry, Boo Berry, and Count Chocula—the monster

cereals. And then there was a Cheerios commercial. And Frankenberry, at the

time they had Battlestar Galactica cards in the box, and so my first line on

camera was, “Viper Fighters in battle!” And then the little girl—who

ended up being one of the girls in the movie Annie—said, “Mine’s

the Battlestar under attack!” And then my second line was, “Let’s

trade!” So that was my first intro to the world of television.