“If

someone doesn’t want to work with me because I’m playing a gay character,

I don’t want to work with them,” he says calmly. “They can

fuck off.”

“If

someone doesn’t want to work with me because I’m playing a gay character,

I don’t want to work with them,” he says calmly. “They can

fuck off.”News - Feature Stories - Magazine - Gale Harold

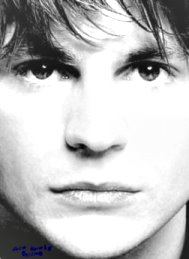

Gale Force

“If

someone doesn’t want to work with me because I’m playing a gay character,

I don’t want to work with them,” he says calmly. “They can

fuck off.”

“If

someone doesn’t want to work with me because I’m playing a gay character,

I don’t want to work with them,” he says calmly. “They can

fuck off.”

Even that succinct statement is more than Harold made to the press when Queer as Folk began. As speculation swirled about which of the actors were actually queer folk, Peter Paige and Randy Harrison identified as gay, Scott Lowell talked about his wife, and Hal Sparks discussed his instinctive discomfort during man-on-man sex scenes.

Gale Harold said…nothing. Friends still fax him items pulled off the Net, comments that he allegedly made in interviews, “basically putting me in line with other heterosexual actors and their comments.” But Harold continues as he started. He doesn’t want to make what he calls “pretentious” comments on gay life, heterosexual life, or his own love life.

“Gale is totally cool and secure enough not to be threatened by anything,” adds Ron Cowen. “He knows who he is. That makes him more than an actor; it makes him a very fine human being.”

Another question that comes up constantly involves the nudity and the sex with other men. But the question people never manage to ask, though they want to, is “How on earth do you manage it?”—the implication being “Doesn’t it disgust you as a straight man?” Rather than addressing that homophobic question, the man who rocked Middle America in the first episode of Queer as Folk (when his character boldly instructed Randy Harrison’s character on rimming) is matter-of-fact about the mechanics of on-screen sex.

“We

have a really good crew,” he says casually. “Between the actors

and the cooperation of the producers, we’ve been able to establish a protocol

for the show, where every sex scene has a ‘sex meeting.’ The director

has a shot list of what he wants. It not only demystifies it, but it’s

like a rehearsal for scenes that aren’t rehearsed. If you know what you’re

going to do and why, when you’re actually there doing it, you can. You’re

not thinking, What the fuck is going on? Where’s the camera? Why are we

rolling again? Why am I doing this again? You don’t have to deal with

it. You understand the scene.”

“We

have a really good crew,” he says casually. “Between the actors

and the cooperation of the producers, we’ve been able to establish a protocol

for the show, where every sex scene has a ‘sex meeting.’ The director

has a shot list of what he wants. It not only demystifies it, but it’s

like a rehearsal for scenes that aren’t rehearsed. If you know what you’re

going to do and why, when you’re actually there doing it, you can. You’re

not thinking, What the fuck is going on? Where’s the camera? Why are we

rolling again? Why am I doing this again? You don’t have to deal with

it. You understand the scene.”

Harold is amused by the responses he gets in public. Heterosexual women beg him to tell them he’s straight. As for heterosexual men, he says, “The responses range from ‘My wife loves the show!’ to ‘I loved the show; it’s funny as hell!’” Gay men love or loathe Brian Kinney, and Harold sometimes gets the runoff. Example? At a Toronto Film Festival party, he heard an expletive fired his way as he passed a group of men he didn’t know. “But you can’t even acknowledge that as a negative response, really,” Harold says philosophically.

His family, for their part, seem to have taken his newfound high profile and growing fame in stride. “Some of them were shocked,” Harold muses, “just by the fact that I had a job. I just let the information come out [bit by bit], so that by the time they actually realized I was on a television show with a budget and that I was getting paid and flying first class in airplanes, they were, like, ‘Jesus, that’s beyond anything we’ve ever considered.’”

The key to understanding Gale Harold is likely not going to be found in this interview, or in any of the other interviews he’s sat for since he became “Brian on Queer as Folk.” It might instead be found by examining where he went while on summer hiatus, before the new season began shooting.

Instead

of heading off to Los Angeles to capitalize on his Brian Kinney status, Harold

packed up and headed to the tiny SoHo Playhouse in New York to appear with George

Morfogen in a low-budget production of Austin Pendleton’s AIDS drama,

Uncle Bob. The stage was his first love, and he had arranged a summer tryst.

Instead

of heading off to Los Angeles to capitalize on his Brian Kinney status, Harold

packed up and headed to the tiny SoHo Playhouse in New York to appear with George

Morfogen in a low-budget production of Austin Pendleton’s AIDS drama,

Uncle Bob. The stage was his first love, and he had arranged a summer tryst.

His personal publicity from Queer as Folk followed him to New York as he tried to prepare for his stage role. “It was very distracting,” he says. “It was a blessing and curse. I wish it had just been the director and I.”

Has he ever woken up and asked himself what he thought he was doing when he took on a role as potentially defining as Brian Kinney? “I haven’t, no,” he answers. “I’ve woken up after seeing this,” he adds, brandishing a page from a high-fashion magazine featuring him sulking elegantly for the camera, “and asked myself what I thought I was doing. Or seeing my cover for MetroSource, which was such a cheese dish, and said ‘What the fuck am I doing? I’m supposed to be working on a play!’”

A publicist knocks on the door to see how the interview is going thus far. Harold smiles with genuine courtesy, but at that moment, it’s clear there’s one place he wants to be—back at work on the set, acting. He’s right: Interviews can be an enormous cheese dish.

“If anyone can crack the publicity nut and figure out how to not come across hammy and contrived,” he says, sighing, “I’d love to talk to them.”

Rowe is author of the essay collection Looking for Brothers.